Key Takeaways

- What Are Enlarged and Swollen Esophageal Veins?

- Causes of Enlarged and Swollen Esophageal Veins

- Symptoms of Enlarged and Swollen Esophageal Veins

- Diagnosing Enlarged and Swollen Esophageal Veins

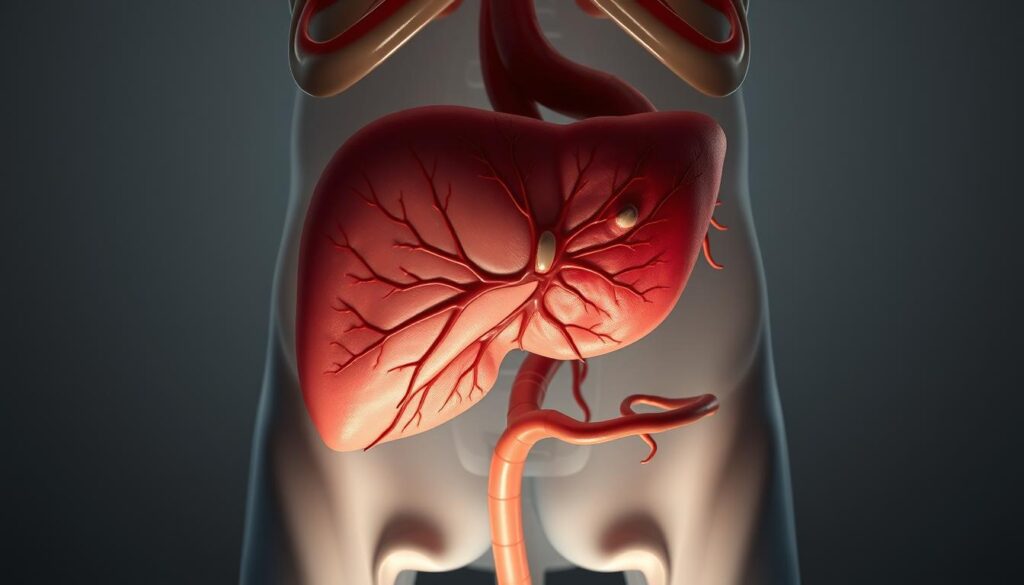

Esophageal varices are abnormal, dilated blood vessels that form in the lower part of the esophagus. They develop when increased pressure in the portal vein system, known as portal hypertension, forces blood to reroute through smaller vessels. This condition is most commonly linked to chronic liver disease.

When left untreated, these fragile vessels can rupture, leading to severe bleeding. The mortality rate during the first bleeding episode exceeds 20%, making early detection critical. Medical guidelines from institutions like the Cleveland Clinic recommend routine endoscopic screening for high-risk patients.

Diagnosis involves assessing portal vein pressure, which becomes dangerous when exceeding 12 mmHg. Approximately half of cirrhosis patients develop varices within a decade of diagnosis. Treatment focuses on reducing blood pressure and preventing life-threatening complications.

Key Takeaways

- Esophageal varices result from portal hypertension, often due to liver disease.

- Ruptured varices cause severe bleeding with high mortality rates.

- Portal vein pressure above 12 mmHg increases complication risks.

- Endoscopic screening is vital for early detection in cirrhosis patients.

- Emergency interventions focus on stopping bleeding and lowering pressure.

What Are Enlarged and Swollen Esophageal Veins?

Portal hypertension forces blood into fragile esophageal vessels, creating varices. These abnormal structures pose significant bleeding risks, particularly in patients with advanced liver disease.

Definition of Esophageal Varices

Esophageal varices are dilated submucosal veins resulting from portal hypertension. They typically form in the distal esophagus due to increased blood pressure in the portal vein system. Histopathological changes include venous congestion and vessel wall thinning.

Clinical grading (F1–F3) reflects endoscopic findings:

- F1: Straight, small-caliber veins

- F2: Tortuous, occupying

- F3: Large, coil-like vessels obstructing the lumen

How They Develop in the Esophagus

Cirrhosis-induced scarring liver tissue raises portal vein pressure above 10 mmHg. Blood flow seeks alternative pathways through portosystemic anastomoses, notably the esophageal venous plexus.

CT angiography reveals paraesophageal collateral networks. These vessels lack the structural integrity to handle high-pressure blood flow, making them prone to rupture. UPMC studies document rapid progression in alcoholic cirrhosis cases.

“Variceal formation represents a hemodynamic adaptation to obstructed hepatic circulation.”

Causes of Enlarged and Swollen Esophageal Veins

Cirrhosis-induced vascular changes frequently lead to dangerous complications in the digestive tract. These abnormalities arise when portal hypertension reroutes blood flow through weaker collateral vessels. Research confirms that 90% of cases correlate with advanced liver disease.

Portal Hypertension and Liver Disease

Elevated pressure in the portal vein system exceeds 10 mmHg in most patients. This forces blood into smaller vessels, including the esophageal plexus. Key hemodynamic studies show a 40% reduction in hepatic blood flow precedes variceal formation.

Cirrhosis as the Primary Risk Factor

Chronic liver damage triggers a pathological cascade:

- Hepatocyte necrosis: Cell death initiates scarring.

- Fibrogenesis: Collagen deposits distort liver architecture.

- Sinusoidal dysfunction: Impaired filtration raises vein pressure.

Compensated cirrhosis patients face an 85% likelihood of developing varices within a decade.

Other Contributing Conditions

Non-cirrhotic etiologies include:

- Portal vein thrombosis: Blocks main vessel drainage.

- Schistosomiasis: Parasitic infection causes granulomatous inflammation.

- Budd-Chiari syndrome: Hepatic vein obstruction.

“HVPG measurements above 12 mmHg predict bleeding events with 92% specificity.”

Symptoms of Enlarged and Swollen Esophageal Veins

Clinical manifestations of esophageal varices often remain subtle until life-threatening hemorrhage occurs. Portal hypertension progresses silently, with bleeding episodes serving as the first detectable symptoms in 70% of cases. Johns Hopkins studies note that variceal rupture accounts for 30% of cirrhosis-related deaths.

Signs of Bleeding Varices

Acute hemorrhage presents with:

- Hematemesis: Bright red or coffee-ground vomiting blood due to upper GI bleeding.

- Melena: Black tarry stools from digested blood, distinct from hematochezia.

- Hemodynamic shock: Systolic BP 100 bpm (UPMC criteria).

Forrest Ia active spurting on endoscopy warrants immediate intervention. A MELD score >18 correlates with 30% mortality during initial bleeding events.

When to Seek Immediate Medical Care

Patients require emergency evaluation for:

- Volume depletion signs (cool extremities, oliguria).

- Hemoglobin 25 mg/dL.

- Altered mental status from hypovolemic shock.

“ABCDE stabilization protocols reduce mortality by 22% when initiated within 30 minutes of hematemesis.”

Quantitative blood loss exceeding 2L activates massive transfusion protocols. Central venous pressure (CVP) monitoring guides fluid resuscitation thresholds.

Diagnosing Enlarged and Swollen Esophageal Veins

Modern diagnostic protocols for portal hypertension complications integrate invasive and non-invasive assessment methods. Multidisciplinary teams utilize endoscopic visualization, radiologic scans, and laboratory tests to stratify bleeding risks. The Japanese Research Society criteria provide standardized classification for clinical decision-making.

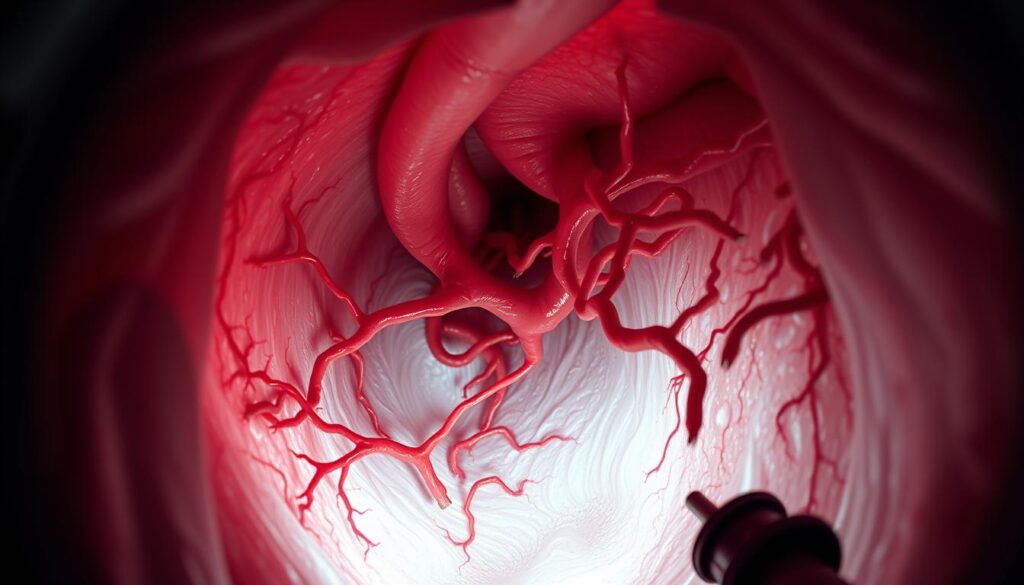

Upper Endoscopy Procedure

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) remains the gold standard for direct visualization. The procedure achieves 85-90% initial hemostasis when combined with banding, per UPMC studies. Key endoscopic findings include:

- NIEC index: Predicts bleeding risk based on vessel size and red wale markings

- Forrest classification: Guides intervention urgency for active hemorrhage

- Variceal grading: F1-F3 scale correlates with pressure thresholds

Imaging Tests

Cross-sectional modalities complement endoscopic evaluation. Multiphase CT with hepatic venous protocol detects vessels >5mm with 92% sensitivity. Additional techniques include:

- Doppler ultrasound: Portal vein velocity

- MRI elastography: Liver stiffness >25 kPa suggests advanced fibrosis

- Angiography: Maps collateral circulation for surgical planning

Blood Tests and Liver Function Assessment

Serologic markers help stage underlying liver disease. Platelet count 1.5 signal significant portal hypertension. Critical laboratory evaluations include:

- ALT/AST ratio:

- MELD-Na score: Guides surveillance interval determination

- Albumin-bilirubin: Predicts decompensation risk

“Combining HVPG measurement with capsule endoscopy improves detection of small varices by 37% compared to EGD alone.”

Treatment Options for Enlarged and Swollen Esophageal Veins

Clinical management of portal hypertension complications requires tailored therapeutic strategies. Treatment protocols prioritize hemorrhage prevention while addressing underlying causes. Multidisciplinary teams select interventions based on bleeding risk, liver function, and patient stability.

Medications to Reduce Bleeding Risk

Non-selective beta blockers (NSBBs) remain first-line treatment for primary prophylaxis. Carvedilol demonstrates superior efficacy, achieving 25% HVPG reduction in 60% of patients. This dual alpha/beta antagonist lowers blood pressure more effectively than propranolol.

Secondary prevention combines NSBBs with endoscopic banding. Current guidelines recommend carvedilol doses of 6.25-12.5 mg twice daily. Antibiotic prophylaxis with IV ceftriaxone reduces infection risks during acute bleeding episodes.

Endoscopic Therapies

Endoscopic therapies provide direct intervention for high-risk lesions. Band ligation using multi-band devices achieves 90% initial hemostasis rates. Sclerotherapy serves as an alternative when anatomical constraints prevent banding.

Technical specifications include:

- Minimum 6-band deployment per session

- 2-week intervals between procedures

- Post-procedure proton pump inhibitor coverage

Surgical Interventions

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) placement reduces portal pressure gradients below 12 mmHg. Covered stents maintain 85% one-year patency rates at UPMC centers. This surgery bridges patients to potential transplant.

Liver transplantation offers definitive treatment for eligible candidates. MELD exception points accelerate waitlist priority for refractory bleeding. Current one-year survival exceeds 85% with proper candidate selection.

“Combination therapy with NSBBs and endoscopic banding reduces rebleeding rates by 40% compared to monotherapy.”

Conclusion

Recent advancements in hepatology have transformed care for high-risk patients. Current AASLD and EASL guidelines emphasize multidisciplinary teams to optimize treatment outcomes. These protocols integrate endoscopic surveillance with pharmacologic risk reduction.

Emerging therapies, like anticoagulation for PVT-related portal hypertension, show promise. UPMC data confirms a 40% decrease in rebleeding with structured care. Long-term liver management requires tailored endoscopic intervals.

Future innovations aim to refine non-invasive monitoring. For now, evidence-based strategies remain vital in improving patient survival and quality of life.

FAQ

What are esophageal varices?

Esophageal varices are abnormal, enlarged blood vessels in the lower esophagus. They develop due to increased pressure in the portal vein, often linked to liver disease.

What causes esophageal varices to form?

The primary cause is portal hypertension, usually from cirrhosis. Other contributing factors include blood clots or severe liver scarring that disrupts normal blood flow.

What are the warning signs of bleeding varices?

Vomiting blood, black or tarry stools, dizziness, and rapid heart rate indicate possible bleeding. Immediate medical attention is required in these cases.

How are esophageal varices diagnosed?

An upper endoscopy is the most accurate method. Imaging tests like CT scans or ultrasounds may also assess liver condition and blood flow abnormalities.

What treatments are available for esophageal varices?

Options include beta-blockers to reduce pressure, endoscopic banding to prevent bleeding, or surgical procedures like TIPS for severe cases. A liver transplant may be necessary in advanced liver disease.

Can esophageal varices be prevented?

Managing underlying liver disease and avoiding alcohol can lower risk. Regular monitoring with endoscopy helps detect varices early in high-risk patients.